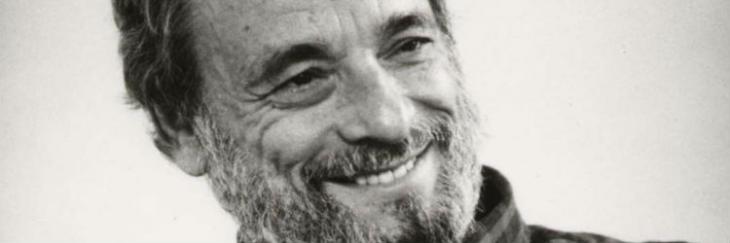

Mark Shenton: How Stephen Sondheim revolutionised the musical

Writers are sometimes loathe to describe their own artistic process, for fear of chasing the muse away. But Stephen Sondheim - whose reputation as the most influential Broadway composer of the second half of the last century is now unassailable - attempted just that, in his 1984 masterpiece Sunday in the Park with George, about the life of pointillist painter Georges Seurat and the process by which he came to paint his greatest work.

In the show, a contemporary descendant of the artist sings: "Bit by bit, putting it together/ Piece by piece, only way to make a work of art/Every moment makes a contribution/Every little detail plays a part/Having just a vision's no solution/Everything depends on execution/Putting it together, that's what counts".

And Sondheim has himself not just put together some of the greatest of all modern musicals, but also pulled the form apart in new and revolutionary ways.

A few years ago I interviewed Jeremy Sams, the British theatre director, noted translator and musician who directed the UK premiere of Passion with Michael Ball and Maria Friedman. He said of Sondheim, "I venerate him as a human being and an artist, and the only thing I have against him is that he's covered every exit and nailed it up, and it's very, very hard for everybody else. I've been listening to a lot of new musicals recently, and they either sound like Stephen or they've been so influenced by him that his ghost is there in absentia. He is as big to musicals as Wagner is to opera, and the history of the musical will never be the same again until he is written out of it. That will take a century."

When I led a public interview with him at the National Theatre in 2004, when that theatre revived A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, I quoted that to him, and he replied, "He's a friend!" I pressed him on whether it is hard to carry that legacy, and he replied, "I don't think of that. I don't see myself from a bird's-eye viewpoint. It's very complimentary, but you know, the good news about what's happening to musicals is that there's much more talent out there, both in New York and in London. People have really inventive ideas about how to use the stage, how to use music, how to incorporate pop music into a musical theatre tradition, ways of involving an audience that are unconventional."

However, he was wary about the current state of play: "There's no place to put them on in London, and no money to put them on in New York. The theatre-going public in New York is not interested in anything that they haven't seen before, and I fear that that's happening here too. This phrase, the "dumbing down of America", the whole culture is getting less interesting, and theatre-going is very expensive. People are less willing to take a chance on something that either they haven't heard about or isn't a hot ticket. They'd much rather see a revival of a show they really like, or a compilation of songs by, say, ABBA — Mamma Mia is a huge hit."

This was, of course, before Hamilton - and in 2015, Sondheim told the New York Times, "Hamilton is a breakthrough." But he added, "It doesn't exactly introduce a new era. Nothing introduces an era. What it does is empower people to think differently. There's always got to be an innovator, somebody who experiments first with new forms."

And that is exactly what Sondheim has done, time and again. In a body of work that began with contributing lyrics only to West Side Story in 1957 (to music by Leonard Bernstein) and Gypsy in 1959 (music by Jule Styne) to A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (the first show he wrote music and lyrics for to be produced on Broadway in 1962) and Road Show (the newest of his shows to be premiered in New York in 2008), his career has had an extraordinary longevity and creativity. He's won more Tony Awards than any other composer, including a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Theatre in 2008; but though he's a critic's darling, he's never quite managed to match the commercial success of say, Andrew Lloyd Webber or Claude Michel Schonberg who wrote Les Miserables.

Nevertheless, his shows are now in seemingly endless revival, particularly those from his most fertile and extraordinary decade, the 70s, in which he truly dominated the form and broke new ground again and again, working each time with director Hal Prince -- starting with Company (1970) and continuing with Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), Pacific Overtures (1976) and of course Sweeney Todd (1979), arguably his greatest masterpiece, each of which I have seen - or will shortly see - again in the last twelve months or the coming twelve.

Most excitingly - and enticingly - are the first two titles of that decade, Company (which director Marianne Elliott will direct for her new company, with the protagonist Bobby played for the first time by a woman Rosalie Craig, breaking new ground again) and Follies (coming to the National Theatre from 22nd August in a production starring Imelda Staunton, Philip Quast and Janie Dee - Sondheim veterans all).

Meanwhile, A Little Night Music is about be revived at Newbury's Watermill Theatre from 27th July; while in New York, the wonderful "Tooting pie shop" version of Sweeney Todd - played in an intimate recreation of an actual London pie shop - is running at off-Broadway's Barrow Street Theatre.

Each musical, whether set in modern-day New York (Company and Follies, the latter with a glance over its shoulder to an earlier era) or 19th century Imperial, isolationist Japan (Pacific Overtures) and Victorian London past (Sweeney Todd), re-made the musical and its possibilities.

It was a spirit of adventure that Sondheim's producers helped forge, in an environment where Broadway was still the creative hub of the American theatre. As Sondheim told me at the National, "I was brought up on Broadway and in Broadway houses. Off-Broadway wasn't even invented till I was in my early 20s, and that was the first time shows were presented anywhere in New York except near Times Square."

Both Hamilton and Rent were born off-Broadway - as were Sondheim's Sunday in the Park with George and Assassins, while Road Show also saw its first New York presentation off-Broadway after premiering (under a different title Bounce) regionally. So Sondheim has moved, of necessity, with the times.

He sees hope in what's going on now. In an interview in the New York Times, he cites Hamilton's success, and attributes part of it to the fact that "Lin-Manuel's use of rap is that he's got one foot in the past. He knows theatre. He respects and understands the value of good rhyming, without which the lines tend to flatten out."

And in a separate interview with Billboard in 2015 he said, "Most new stuff is new but not as skilled as Hamilton. Lin knows how to write a song, and so did Jonathan Larson. Rent was the perfect example of a guy with one foot in the past, one foot in the present and a third foot in the future, but it's mostly in the present." Sondheim could have been describing himself. And the joy is that he is ever-present in our theatre today.

Stephen Sondheim's Follies will run at the National Theatre from 22nd August.

Originally published on