A Midsummer Night's Dream - RSC 2006

A play with a 'weak and idle theme' is how Shakespeare (through the character of Puck) described his play 'A Midsummer Night's Dream'. And who am I to argue with that? Because this comedy, focusing on fairies, weddings and the bungling acting aspirations of a group of tradesmen, borders on farce for much of the time, and seems to stretch an audience's tolerance to extremes (which is the reason why Puck at the end of the play is so anxious to obtain forgiveness). But it's really an endearing, light-hearted play that leaves even the most cynical with a fairly high 'feel-good' factor at the end of it. With a large cast and ample room for imaginative use of comedy, it's not hard to see why 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' is one of the most frequently performed of Shakespeare's plays. And it's the comedic element which this version by the Royal Shakespeare Company refines, enhances and milks almost to perfection.

Containing some of Shakespeare's favourite devices and themes (for example, forests and a 'play within a play') the plot is a contrasting concoction, blending the trials of love with the magical quality of dreams. But it begins firmly rooted in realistic, legal formality. Theseus, Duke of Athens, is about to marry Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons. Egeus takes his daughter, Hermia, to the Duke because she's refusing to marry her father's chosen suitor, Demetrius, because she's in love with Lysander. According to Athenian law, Hermia has to marry Demetrius, live the rest of her life in celibacy, or face death (a pretty lousy choice if ever there was one). So Hermia and Lysander decide to elope, and plan to meet up in the nearby woods, which are coincidentally inhabited by a band of fairies that are invisible to humans. Demetrius, who's also in love with Hermia, and Helena who's in love with Demetrius follow them there. Trouble is also brewing in the fairy brigade, because Queen of the fairies, Titania, is refusing to hand over her boy page to Oberon, King of the fairies. In retaliation, Oberon gets one of his fairy minions, Puck, to pour the juice of a plant into Titania's eyes so that she'll fall in love with the first thing she sees on waking - that happens to be Bottom, the weaver, one of a band of tradesmen (or 'rude mechanicals' as Puck calls them) who've repaired to the woods to rehearse a play, which they intend presenting to the Duke after his wedding. As a joke, Puck has turned Bottom's head into that of an ass, yet when Titania wakes, she finds him irresistible. With both the humans and Titania in confusion, it falls to Oberon to sort out the mess.

A large sphere representing both sun and moon (and, in a sense, nature itself), dominates Stephen Brimson Lewis's set for the duration of the play. And a clinically white, box-like Ducal palace provides the essential bland contrast with the mysterious, if not threatening, woods of the fairy kingdom, where a Womble-like collection of dustbin lids and jetsam provides an eerie background.

Gregory Doran's direction reveals painstaking attention to detail, which is remarkably enriching and effective. It's most clearly seen in some of the business, for example a clever, and brilliantly timed slapping sequence when the ill-matched lovers are sitting in the forest, as well as in the imaginative treatment of the 'play' during the finale. We also see it in the pacing during the scene where we're introduced to the Brummie tradesmen.

But Doran's production also encapsulates a very real sense of fun, perhaps reflecting the company's experience in developing it. It's evident in Joe Dixon's sympathetically proud Oberon who can't quite hide a wry smile when watching the antics of the humans - and in Jonathon Slinger's excellent Puck, who appropriately observes "What fools these mortals be". And the fun even extends in a more subtle way to the costumes - Bottom wears what we English call a 'donkey jacket' (a distinctive black workman's coat with plastic covering the shoulders). And during the tradesmen's performance of their play before the Duke of Athens, he wears a brush head on his helmet.

The striking finale of 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' is the tradesmen's 'play', which provides a particularly hilarious highlight to this joyous production. As any director would, Doran carefully wrings the comedy from this scene by exploiting the incompetence of the inept tradesmen 'actors', but with an innovative twist. In the midst of their dire performance, one of the tradesmen, Flute (played by Jamie Ballard) suddenly finds himself engrossed in his role to the extent that he's overcome by emotion and close to tears, causing his startled comrades to glare round the curtain in amazement - sheer brilliance in terms of both direction and acting, and a highly fitting conclusion to a comedic delight.

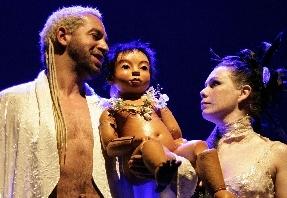

Production photo by Stewart Hemley

Originally published on