'The House of Bernarda Alba' review – Harriet Walter anchors a wrenching tragedy of female oppression

Read our four-star review of The House of Bernarda Alba, directed by Rebecca Frecknall, now in performances at the National Theatre to 6 January.

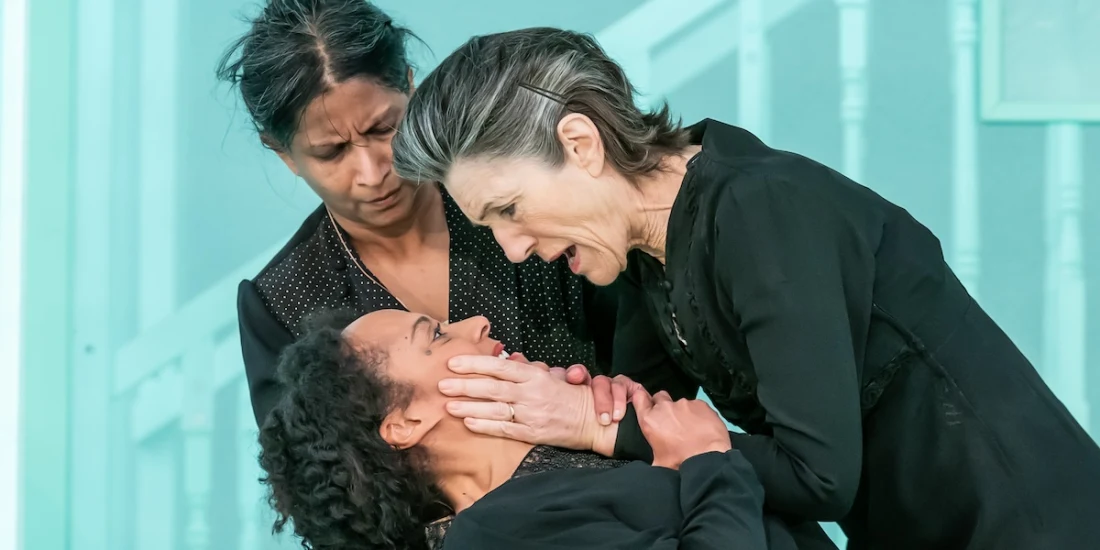

Harriet Walter has recently cornered the market for warped maternal figures, from Succession and Ted Lasso to the iron-willed matriarch of Lorca’s play. It’s another towering performance, but Rebecca Frecknall’s striking production is very much an ensemble piece: a portrait of a family, and a patriarchal society, that oppresses, confines and destroys women.

In 1930s fascist Spain, the widowed Bernarda Alba enforces eight years of mourning upon her unmarried daughters. They are imprisoned inside – stunningly illustrated via Merle Hensel’s doll’s-house set, its clinincal white and cool mint-green contrasting with its occupants’ frustrated passions. Each bedroom looks like a cell (either jail or convent), dominated by a crucifix, while the yard is bookended with iron gates.

Alice Birch’s pithy, acerbic adaptation (excellent apart from its jarring overuse of F-words) is sharply attuned to how women can become unwitting agents of misogyny. Bernarda is so concerned with protecting her girls from the vicious world of men that she cuts off their oxygen altogether. She places unfair judgements on them, while relishing tales of other, less virtuous girls who are violently punished.

The daughters, instead of banding together, grow jealous and petty, and compete for male attention. No matter that it comes in the form of village lothario Pepe El Romano, who proposes to Angustias for her large dowry, but secretly seduces her younger sister. Meanwhile Bernarda’s senile mother (a vivid Eileen Nicholas) wanders the house in her wedding dress, seeking freedom.

Frecknall, making a fantastic National Theatre debut following her hit productions of Cabaret and A Streetcar Named Desire, again uses movement brilliantly. Pepe invades the house in dream sequences, as does the ferocious village mob that killed a local girl who got pregnant out of wedlock. Peter Rice’s soundscape, with foreboding music by Isobel Waller-Bridge, makes your skin crawl.

Youngest daughter Adela dances with disaster, whirling in the yard until she falls to the ground, or clambering the gate for a clandestine embrace. She screams out that she needs to be in control of her own body – words that crash through the decades to feel horrifically relevant to 2023.

Isis Hainsworth, such a force in Frecknall’s Romeo and Juliet, is similarly potent here: a spitting, clawing ball of hormones, dreams and rage. Lizzie Annis is agonising as the disregarded, disabled Martirio, who, poisoned with envy, betrays her sister.

Birch’s adaptation gives Angustias a keener motive to escape this family and never look back, suggesting that she was sexually abused by her stepfather. Rosalind Eleazar plays her as a wary survivor. It makes an interesting contrast with Pearl Chanda’s careless, attention-seeking Magdalena, who faints, weeps and relishes voicing what no one else will.

But perhaps the most fascinating dynamic is between Walter’s steely Bernarda and servant Poncia (an equally commanding Thusitha Jayasundera). It’s the one area where the snobbish Bernarda breaks the rules: she confides in her like a friend. Yet she won’t believe Poncia when she predicts the coming storm, instead staying wilfully blind to it, terrified of something she can’t control.

Yet that fear pushes her to horribly cruel acts. When she says that a disobedient daughter “is no longer a daughter,” you believe it; her chastisements include plunging her child’s arm into a pot of boiling water. She sacrifices them all to uphold tradition – the “house” of the title becomes all-consuming.

It’s a wrenching watch, a mix of contemporary and ancient, social and elemental tragedy, and a grim demonstration of how, as Birch puts it, simply being born a woman can feel like the greatest punishment. Bernarda’s climactic call for “silence” is the final stifling of a desperate female cry.

The House of Bernarda Alba is at the National Theatre through 6 January.

Photo credit: The House of Bernarda Alba (Photo by Marc Brenner)

Originally published on