Remembering Stephen Sondheim: the legendary writer's lasting impact

"Every Day a Little Death," goes a song from A Little Night Music, but last Friday came news of a big death: the passing at age 91 of that show's creator, Stephen Sondheim, who just the previous day was said to have enjoyed Thanksgiving dinner with friends. The suggestion, as a result, is that the great man went quickly and, let us hope, painlessly, leaving the musical theatre industry to ponder the absence of someone who, it often seemed, would be with us forever. As his work undoubtedly will be.

There's been abundant mourning, and rightly so, in New York where Sondheim is represented just now with revivals of both Assassins and Company — both of them, as it happens, under the auspices of British directors, John Doyle and Marianne Elliott, respectively. The current Company marks the American debut of the gender-flipped rewrite of that show, which I saw six times during its acclaimed London run — a properly tumultuous closing night included. That performance was interesting for, amongst other things, its composer's decision not to take the prime stalls seats that had been allocated specifically for him (and that happened to be right in front of me). Instead, he and his guest sat to one side up in the circle. Why? The reason proffered at the time makes good sense: Sondheim wanted the attention that night to be on a cast who would be coming together one last time, without his own centre-stalls presence, as it were, to deflect focus from the stage. (Of that superlative London ensemble, only Olivier Award-winner Patti LuPone, its lone American, has travelled with the show to Broadway.)

As it happens, Sondheim's presence somewhere in a theatre, his work represented on one or another a London stage, has been one of the thrills over the past 30-plus years of my residency in London. As an American who long ago chose to make London home, I expected to be awash in Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Shaw and exciting new plays by Tom Stoppard or Caryl Churchill or Roy Williams or Jez Butterworth. But even my acquaintanceship as a theatre-mad teenager with the Broadway transfer of Side by Side by Sondheim - a musical revue spawned in Britain - couldn't have prepared me for the breadth of this city's interest in someone frequently billed this side of the pond as "the American Shakespeare." That accolade, glib though it may seem at first, gained weight, I thought, when spoken by a theatre populace marinated in Shakespeare that knows whereof it exalts - even if, in my view, Sondheim exists closer to an American Chekhov in his full embrace of the byways of love and loss, passion and pain.

When it came to Sondheim, London was hellbent on discovery: the 1997 premiere, for instance, of Sondheim's Saturday Night, a curiosity from the 1950s which only then was seen in New York. Or a Sweeney Todd, directed by the Scotsman behind Assassins, Doyle, that made musicians out of its cast of thesps, an approach subsequently applied to both that musical and Company on Broadway, as appraised anew by Doyle's watchful eye. Time and again, reclamation and revitalisation have accompanied many a Sondheim staging: Follies in 1987 boasting a clutch of new songs - some of them later discarded, every single one of them fascinating - for its West End debut, or Company at the Donmar, directed by Sam Mendes and with an astonishingly open-hearted Adrian Lester as the first Black actor to play that role, at least in any major production.

By the time Marianne Elliott got to casting the peerless Rosalie Craig as the questing Bobbie, the decision to gender-flip the role seemed of a piece with the author's own desire never to take the familiar path. "The road you didn't take" is a life choice cited in Follies but seemed equally well to be the implicit mantra underpinning British approaches to Sondheim. Merrily We Roll Along, for instance, has been performed here with a young cast, at the Donmar as directed by Michael Grandage, and with an adult cast, at the Menier and then on the West End under the empathic eye of Maria Friedman, herself one of several British performers - Julia McKenzie and Imelda Staunton are others - who could legitimately merit the label of Sondheim muse.

Many is the British director who has rarely been better than when paired with Sondheim: Jamie Lloyd's fearsome Assassins at the Menier in 2014 remains for me as definitive a reassessment of that show as was his extraordinary Donmar take on Passion, the second of which remains the only production of that tricky piece in my experience to give its male lead, Giorgio, the pride of place he is granted in the writing: indeed, David Thaxton won an Olivier Award for that performance, and rarely was an accolade more richly deserved. Lloyd's Assassins cast, meanwhile, boasted a stellar visiting American in the clarion-voiced Aaron Tveit, playing Booth.

Sondheim's Anglophilia had the unexpected good benefit of bringing him and me together with some frequency. I watched with awe and admiration in 1990 as Sondheim led a series of master classes at St Catherine's College, Oxford, as the first visiting theatre professor there as part of a bequest made possible by Cameron Mackintosh, the same impresario who saw to it several decades later that Shaftesbury Avenue had a Sondheim Theatre of its own to equal the one on Broadway. Those 1990 students were able to pay witness to the birthing for the National Theatre of the UK debut of Sunday in the Park with George: a production, directed by Steven Pimlott, that Sondheim was later reported not to have liked even if it did allow his class to watch the sitzprobe of a Pulitzer prize-winning show with its co-creator in attendance.

Subsequent one-on-one interviews found me at his Turtle Bay home, where he answered my query as to his favourite Momma Rose (my lips are sealed as to his two-person reply, one Rose for each act) and to a London hotel room on a day when he was feeling far from his best but still found time to answer graciously and informatively a volley of questions he had surely heard before. (Watching the new, and excellent, film of tick tick .... Boom!, I laughed out loud at the exactitude with which Bradley Whitford catches the composer's frequent use of the adjective "swell," which from Sondheim represented very high praise indeed.) We shan't hear that word voiced afresh from his lips any longer, which does somehow make the world seem a duller, more prosaic place.

Sondheim claimed many a time not to be interested in legacy, claiming that he wouldn't be around to know what his was in any case. That's fair enough, and characteristically modest as well. But for myself, I can say only that not a day goes by when I am unaware of a bequest that I feel privileged to have experienced first-hand. To paraphrase a signature lyric from Passion, loving Sondheim's work has turned out not to be a choice. Now that he is gone, it's more than ever a part of who I am.

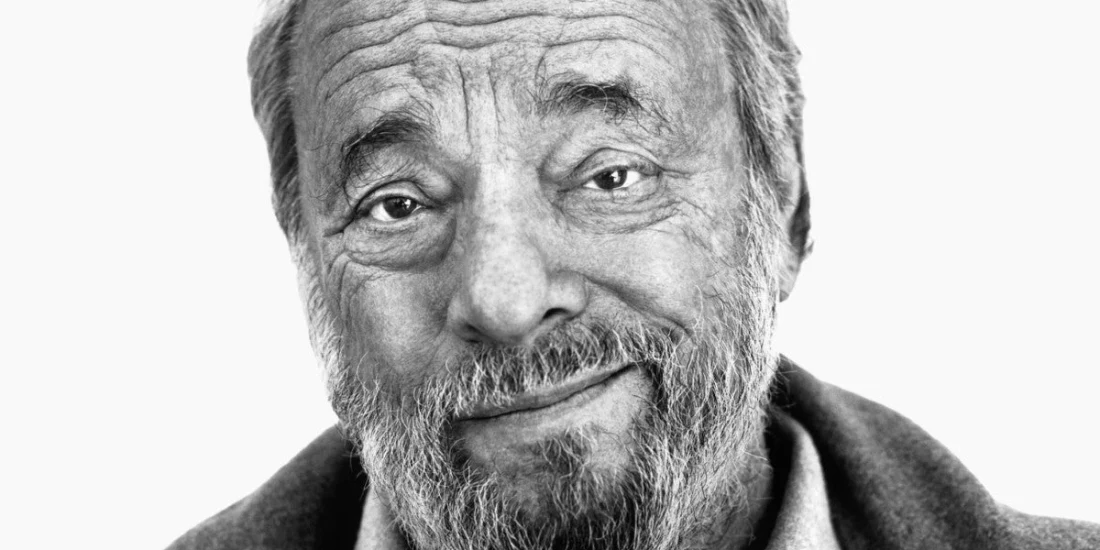

Photo credit: Stephen Sondheim

Originally published on