In Extremis - Shakespeare's Globe 2007

This year's season at the Globe is about Renaissance and Revolution and to start off this revolution it is fitting to come full circle and revive last year's closing play In Extremis.

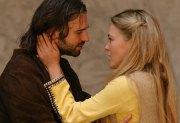

Peter Abelard, a 12th-century, articulate, questioning student uses Aristotelian logic to confound his teachers and undermine establishment theology. When he falls in love with his pupil, bright young Heloise, their affair scandalises clerical circles, produces a child and leads to Abelard's castration and the lovers' enforced separation. But writer Howard Brenton's real interest lies in their intellectual opposition to the Cistercian abbot, Bernard of Clairvaux.

Bernard is a mystic who preaches that the denial of the individual is the true path to a spiritual connection with God, while Abelard maintains that only through the application of logic can we know God better - sowing the seeds of individualism and ushering in the spirit that became the Renaissance. Throughout the play, as the two lovers meet and fall in love, and are then torn away from one another and forced to begin new lives, this argument of spiritualism versus individualism forms the underpinning of the story. Heloise puts it neatly when she describes herself and Abelard as "philosophical warriors" fighting a war of ideas; and all the best scenes in Brenton's play are those of argument.

The rich, meaty contemporary language that Brenton gives to his hero and heroine instantly involves the audience, who are drawn into the philosophical rhetoric. The debate about whether we find God through the contemplation of nature and the universe, or through reason and logic is continued to this day and through one of the greatest love stories of the middle ages, Brenton explores the relationships between logic and religion, humanism and fundamentalism, faith and power.

Jack Laskey's Bernard has a fine mix of the calculating and the possessed, verging on insanity. But Abelard is by no means perfect himself, he is an ambitious, often arrogant, impetuous young man, reveling in the celebrity of being the philosopher of the moment, reminding me a little too much of a pompous English teacher I once had. You want him to win in his battle with the exploitative Bernard, but you're not altogether sorry that he's brought down to earth with a thump. It is the rabid, fundamentalist Bernard, supposedly representing everything Brenton deplores, who emerges as the most gripping figure. Laskey's Bernard lights up the stage, wound-up tight with the frenzied energy of belief. The confrontations between Abelard and Bernard are memorable and not just because their arguments between reason and religious passion have frighteningly modern echoes.

If anything, Sally Bretton's Heloise emerges as the more admirable figure in her combination of intellectual toughness and emotional ardour. Abelard makes clear that as well as falling under the spell of hormones, he had been stunned by the literary genius of Heloise. Unfortunately, despite Brenton having borrowed some of Heloise's own words from her letters for his character: "sweeter for me will always be the word mistress," she is only allowed to flower in the climactic confrontation between Heloise and Bernard. It is only then that her mind really is allowed to show more, to show her truly revolutionary radicalism.

Brenton, director John Dove and the cast manage a fine job with many of the minor characters. Paul Copley's Fulbert, Heloise's silly but proud guardian, performs a finely-tuned balancing act between comedy and tragedy and Colin Hurley plays the knowing, cynical, clever and corpulent Louis VI with relish. The frequent comic scenes are masterfully handled, the beautifully timed toppling of a drunken bishop into minutes-long undignified immobility and the stomach-turning display of Bernard's saintly party piece, the licking of rotting feet, are just two examples of classic Globe stagecraft.

Who would guess that a 21st-century crowd could be listening so intently to philosophical debate from the 12th-century about the nature of the ideal? Unfortunately Brenton's concentration on philosophical discussion sometimes threatens to get in the way of the emotional power of this famous love story. But while many would be daunted by the prospect of two-plus hours observing a medieval play about religion, the injection of numerous bawdy laughs allowed for an engrossing and enjoyable whole and the crowds left pleased. The production masterly interweaves comedy and drama, drawing on the Elizabethan tradition of interacting with a socially mixed crowd in the intimate space of the Globe. There are many Shakespearean echoes, especially the rousing final dance and the onstage band is lively with authentic bells and harp. I must be a literary snob because I had to admit to myself that I still prefer Shakespeare but overall, this is an enlightening performance and the Globe itself more than makes up for any slight disappointments I may have felt.

(Chloe Preece)

Originally published on