Theatre relies on new found pleasures in the classic repertoire

New plays and musicals are the lifeblood of the theatre, endlessly renewing it and keeping it alive, but old work is its bedrock: the deep repertoire of past classics that we draw on again and again to inform the present moment through the lens of writers who've long preceded us.

Sometimes these suddenly feel freshly immediate: who'd have guessed it that the best theatrical explanation of Brexit is being articulated in an 1886 Ibsen play, Rosmersholm, currently being revived at the West End's Duke of York's? In Duncan Macmillan's brilliant new version, a character says, "You see, this is what happens when the general public becomes engaged with politics - they get duped into voting against their own interests."

He also points out, "Look, politics is complicated. The average working man doesn't have the time, inclination or education to fully understand it. So the papers sell them a lie that its actually very simple. That it's not about facts. It's about feelings."

So, too, is the theatre; but it is the theatre critic's role to include the facts as well as the feelings and enable the reader to draw their own conclusions. Rosmersholm turns out to be a bracingly modern rediscovery of a play that's rarely staged. The same can be said of Githa Sowerby's 1912 masterpiece Rutherford and Son, which came back to the London stage last week.

It is part of the occupational hazard of being a critic that you'll inevitably see multiple productions of the same play or musical across a lifetime many times. Most years we're called on to review at least one or two productions of Hamlet and King Lear (and it never gets tired or tiring, either: it has recently been announced that Cush Jumbo will return to the London stage next year to play Hamlet at the Young Vic, and I can hardly wait).

But sometimes I actively search out repeat viewings myself. Last weekend I saw my third new production of Guys and Dolls and my second of Little Shop of Horrors in the last twelve months - purely for the pleasure of seeing them again.

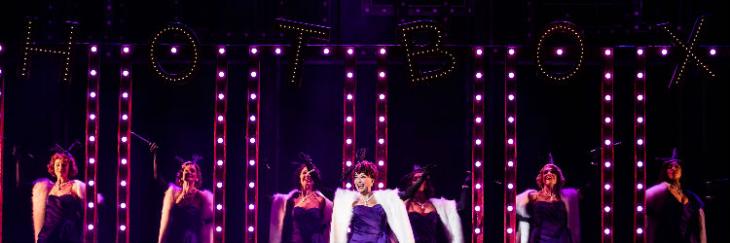

Guys and Dolls is simply a flawless musical: undoubtedly my favourite musical of any in the canon. In Frank Loesser's dazzlingly tuneful score and Abe Burrows's witty distillation of Damon Runyon short stories, it perfectly encapsulates a mythical Broadway of inveterate gamblers, showgirls and mission-dolls, and sends them into thrilling collision with each other.

In the last year, I've seen a wonderful concert version at the Royal Albert Hall as well as a perfect small-scale version at the Mill at Sonning dinner theatre; last Friday I hopped across the channel by Eurostar to Paris to see a new production at the Théâtre Marigny there, directed and choreographed by Stephen Mear (who also staged the Albert Hall concert). In a remarkably bold bit of producing, the Marigny is offering Broadway musicals in their original (i.e. English language) form, with French surtitling.

Even though I can virtually recite every single line of both the book and songs simultaneously with the actors, I find fresh pleasures every time. These are, of course, often performance driven - getting the comedic and singing balances right is often a tall order with this show, but Ria Jones proved to be easily the best Miss Adelaide I've seen since Samantha Spiro took over in the last West End revival at the Phoenix. It felt like she was channelling Bette Midler in a performance of remarkable truthfulness and punch. It was also marvellous watching Christopher Howell as a hilarious Nathan Detroit, Clare Halse as a gorgeously sung Sister Sarah, Matthew Goodgame as a smoothly textured Sky & especially Joel Montague as the warmly engaging Nicely-Nicely.

Meanwhile, at Chester's Storyhouse - a multi-purpose arts complex created out of the shell of a former Odeon cinema that also doubles up as the city's central Library building - Little Shop of Horrors is a littler show, of course, than Guys and Dolls, but full of its own intricate crowd-pleasing pleasures. I've seen this show, too, many times over the years, from its original Off-Broadway run at the Orpheum Theatre downtown in 1982 and its ill-guided Broadway revival in 2003, to another weirdly overblown take at London's Open Air Theatre last year that turned the plant into an over-the-top drag queen.

But scaled back to its proper size at Chester, it reclaimed the surprisingly smart and sophisticated joys of this musical by Alan Menken and his late, much-missed lyricist Howard Ashman, whose words are so quirky and hilarious that they ping and zing with pleasure. (And sound designer Ben Harrison makes sure that every one is crystal clear).

I love both shows unreservedly. And I never get tired of seeing them again and again.

Photo credit: Julien Benhamou

Originally published on